A volume of unpublished letters exchanged between members of Charles Dickens’ family after his death is on display in London. The documents, on display at the Charles Dickens Museum in Kings Cross, reveal the enduring love that the author’s wife Catherine – from whom he had brutally separated – felt for their children.

Even Dickens’s biggest fans and many of his friends in life found his treatment of Catherine difficult to deal with. They married in 1836 when they were both in their twenties and, as an exhibition dedicated to her at the Dickens Museum in 2016 made clear, she was intelligent, kind, a gifted musician and devoted to her ten children. She never uttered a single harsh word in public about her husband’s treatment.

Dickens, on the other hand, abandoned all friends who showed signs of taking her side. He tried to portray her as an incompetent mother, neurotic if not mad. He first moved out of their shared bedroom and had the connecting door nailed shut, and when he officially separated from her in 1858, he took out a newspaper advertisement – something friends begged him not to do – announcing that “some long-standing domestic problems of mine” had been solved. The secret he kept was his relationship with the much younger actress Ellen Ternan.

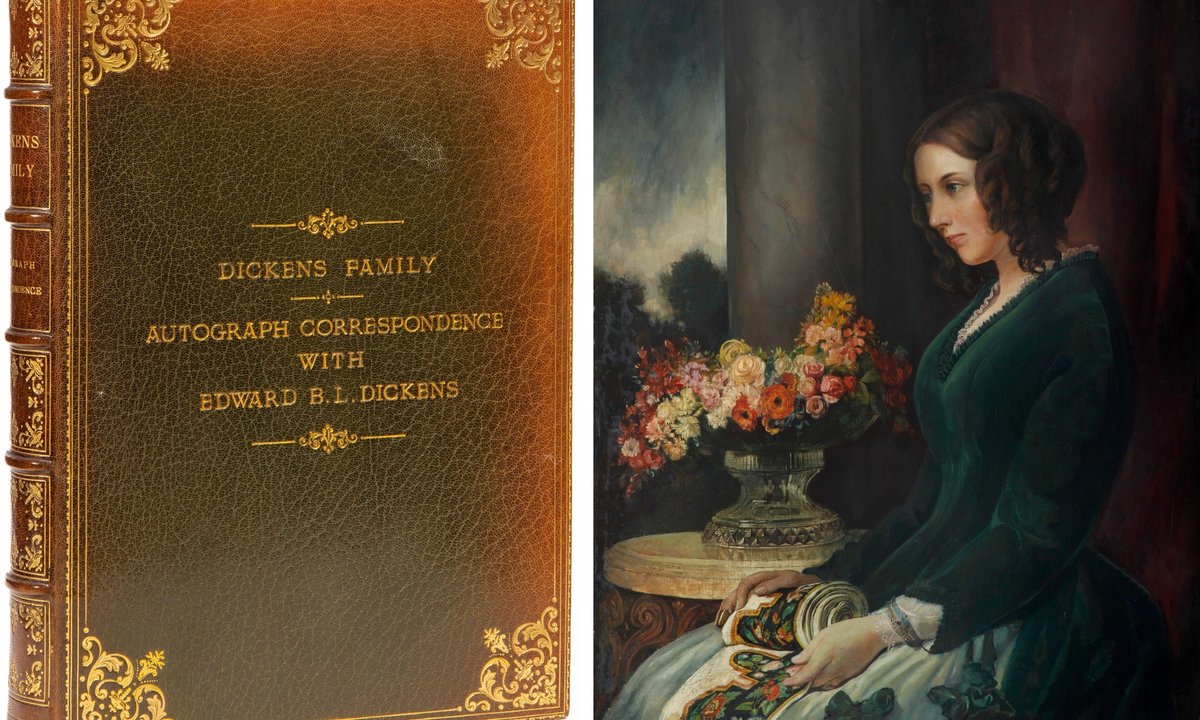

The newly discovered letters, bound in an album that the museum acquired for £5,500 at an auction of the library of William Foyle, founder of the eponymous bookshop, are from Catherine, Dickens’s siblings and aunts of Edward, the youngest of the ten children. Dickens, who nicknamed him Plorn – or Plornishmaroontigoonter in full – encouraged the boy to emigrate to Australia at the age of 16. Plorn was never particularly successful and died there aged 59.

What do the letters reveal about Catherine Dickens?

Catherine’s letters refute Dickens’ claim that Catherine was “a cold and distant mother.” She misses her children and longs to see them more often. They also convey the hope that after her father’s death she may be able to visit them at Gad’s Hill, the house in Kent to which all the children except Charles Junior moved with him from London.

According to Emma Harper, curator of the museum, the objects give Catherine a voice: “This fascinating collection destroys the image that Charles Dickens tried to create when he separated from Catherine Dickens in 1858, accusing her of being an unsuitable wife and mother.”

In many of the letters, the family discusses current events, including the visit of the Shah of Persia and the trial of the Tichborne Claimant – an Australian butcher who sought to lay claim to an aristocratic fortune in England. But one particularly poignant letter explains why Catherine had not been in touch with her for a while.

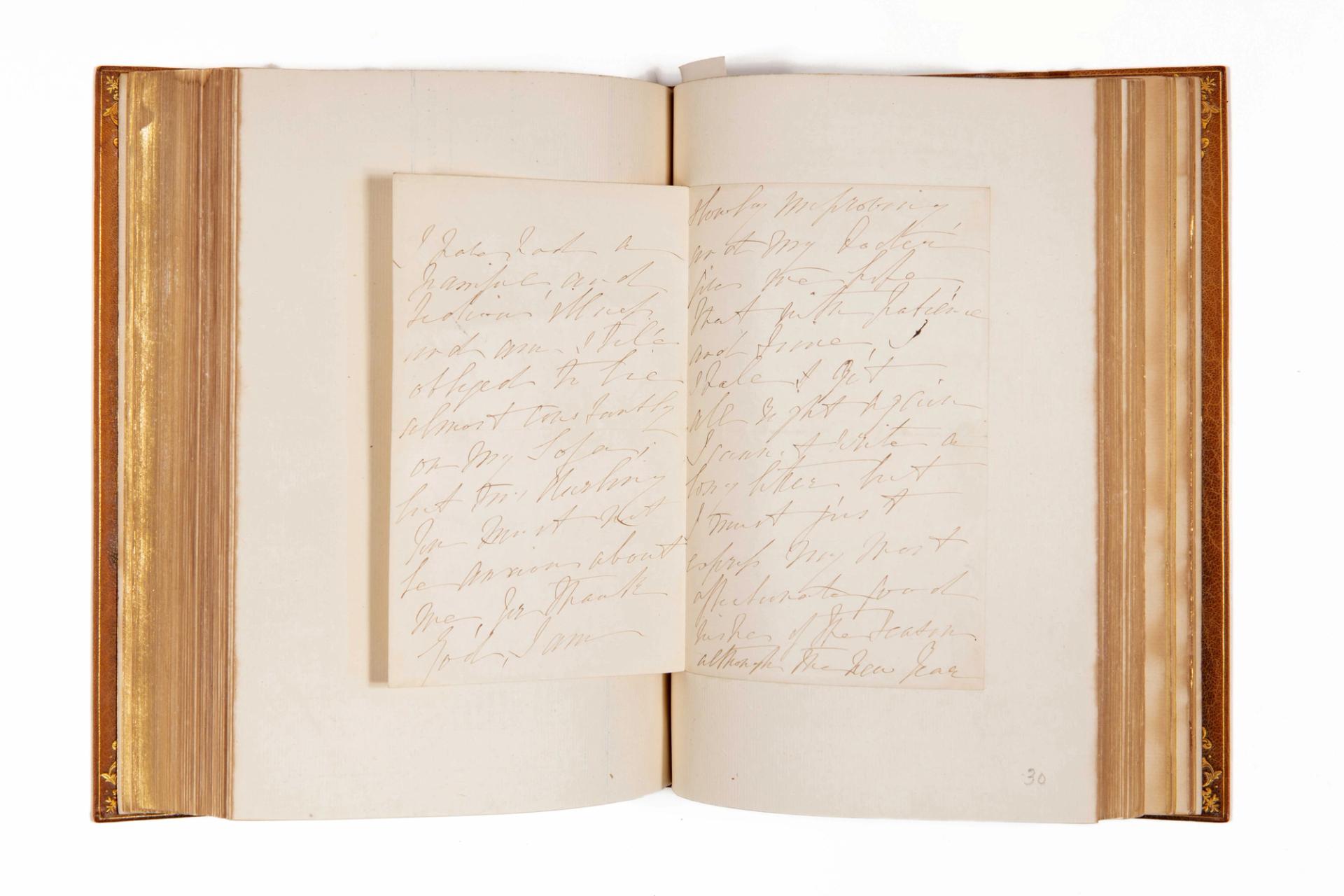

On Christmas Eve 1878 she wrote: “I have had a painful and long illness and still have to lie on my sofa most of the time, but darling, you need not worry about me, for thank God I am slowly getting better and my doctor gives me hope that with a little patience and time I will be well again. I must just offer you my warmest best wishes for the holidays, although the New Year will be a while before you receive them. I cannot tell you how much devoted love and kindness I am receiving from all my dear children during my illness. God bless you, my own Plorn.”

Pages from the letter Catherine sent to Plorn on Christmas Eve 1878

Courtesy of the Charles Dickens Museum

Catherine’s condition did not improve “slowly”. The “protracted illness” was cancer, and she died later that year at the age of just 64. She is buried in Highgate Cemetery, far from Charles’ grave in Westminster Abbey.

The letters are on display until November at the museum in Doughty Street, Dickens’ only surviving London house, where the happy first years of their marriage took place.

Dickens-Macready canvas returns to Dorset

A less emotionally charged relic associated with Charles Dickens has returned to the house where it was made – a four-panel screen that the author and his good friend, the actor William Macready, decorated at Sherborne House in Dorset in the 1850s. The couple used hundreds of prints, scraps and newspaper cuttings, probably as educational stimulation for Macready’s children.

Panels from the Macready Dickens screen, which has returned to its location in Dorset

Dickens was Macready’s guest several times in Sherborne. In 1854 he gave a public reading in aid of the Sherborne Literary and Scientific Institution. Tickets for five shillings initially sold poorly and Macready complained: “A crown, what is that? The price of a bottle of bad wine drunk at a public dinner.” However, after a last-minute price reduction, the hall was described as “crammed and suffocating” while Dickens read for nearly three hours.

The screen remained in the Macready family until 2004, when it was donated to Sherborne by a direct descendant. It was in poor condition, but has now been extensively restored after a local fundraising appeal raised £22,000. Paper restorer Rebecca Donan has deliberately left some damage visible, including a burn mark from someone standing too close at night, and scratch marks from a family pet.

The 18th-century mansion, whose future was uncertain after it closed as an arts centre and was sold by the local authority to a property developer, has now been fully restored by a trust. It reopened this summer as The Sherborne and is open daily, with free entry.