India may be the fastest growing economy in the world but it is not creating enough jobs. This is mainly due to its failure to bring about an industrial revolution. But a success story has recently emerged that is debunking false myths in the minds of our rulers and politicians. It offers many lessons and is also a call to action. Can we replicate it in other labour-intensive sectors?

Since 1991, India has grown at nearly 6% per year for the last 30 years. 450 million people have been lifted out of poverty, while the middle class has increased from 10% to 30% of the population. India has achieved extraordinary success in the services sector, becoming the back office of the world. But manufacturing has failed – it generates less than 15% of GDP, employs 11% of the population and exports 2% of the world’s goods. But no country has been able to lift itself out of poverty without it. The successful nations of East Asia – Japan, Korea and Taiwan – have all followed the same mantra of exporting labour-intensive products. China is the most recent example.

India’s problem is not unemployment, but underemployment. As a result, regular labour market surveys do not reflect the extent of the employment crisis. Too many young people work in low-productivity informal jobs on the farm or in the bazaar, but they aspire to higher quality and more productive work. In the recent Lok Sabha elections, polls suggested a fear of quality jobs, which may partly explain the surprising election result.

There is good news, however. A world leader has chosen India as its second manufacturing base for global supply. Apple’s iPhone was made entirely in China until 2021. Today, the company has created 150,000 direct jobs in India (70% of them for women) and an estimated 450,000 indirect jobs, while producing $14 billion worth of phones and exporting over $10 billion a year. This is just 14% of global iPhone production, which is expected to rise to 26-30% by 2026, according to JP Morgan. Huge dormitories are being built near the contract factories in Tamil Nadu to provide a safe environment for women workers.

To become a viable export hub, India still needs to attract iPhone component manufacturers, who account for 85% of the value added. They are mostly Chinese. They will create far more jobs, impart more skills and transfer more technology. This is the only way to get our SMEs into global value chains. This is what happened years ago with Maruti. A side effect will be to reduce India’s trade deficit with China. Therefore, it is in our national interest to allow Chinese suppliers. Otherwise, every mobile phone sold in India will continue to create jobs in China.

There are many lessons to be learned from this story. First, abandon the false myth that India is a big market. India has a large population whose purchasing power is modest. The common assumption that global brands are lining up to manufacture in India is false. When Apple decided to manufacture in India, phone sales in India were only 0.5% of global sales. The iPhone’s entry into the market was facilitated by empathetic government negotiators who listened to the company’s needs with refreshing openness and humility.

A second lesson is that no country can create enough jobs with its domestic market. China, which has a far larger market, has depended on exports for its success. Import substitution through protection through high tariffs – which has been instilled in Indians since the 1960s – is a bad idea. It perseveres like a disease, making India the tariff master of the world. Unless India reduces its tariffs to competitive levels, it cannot hope to enter the global value chains that account for 70 percent of the $24 trillion global trade in goods. Any PLI scheme should therefore include a sunset clause for high tariffs.

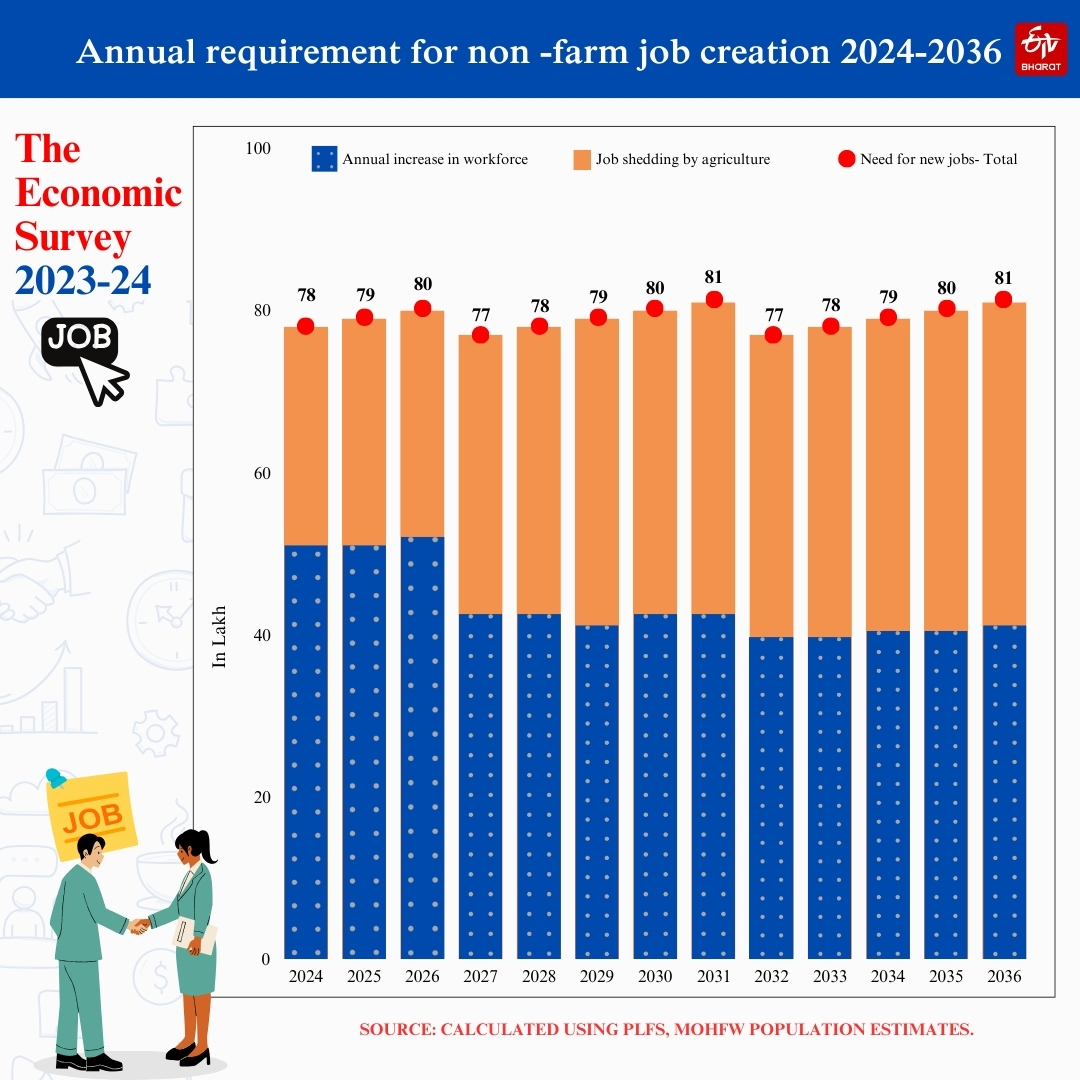

Annual Non-Farm Employment Generation Needs 2024-25 (ETV Bharat)

Third, the driving force behind job creation is not small micro-enterprises, but the large companies that supply the smaller companies. Yes, overall, small companies create far more jobs – and this government is doing the right thing by securing credit for them. But action starts at the top. The government should focus on the leading global brands, especially those that are concerned about the risks of manufacturing in China.

Fourth, the big company need not necessarily be Indian. Once global value chains are in place, they will help national champions to go all over the world. Tata’s involvement in iPhone production is a case in point. To succeed in the global market, you need a superior product. Because Indian companies are chasing tariffs, they have not learned to invest in research and development to create superior products. Hence, there are no Indian global brands. So the first step is to court the leading brands in all labor-intensive sectors and copy the iPhone story.

Fifth, India needs a skilled population but we cannot put the cart before the horse. Most women in iPhone factories only needed 4-6 weeks of training, even if it was their first job. The big mistake of our training institutions (like ITI and Skills Missions) is disconnection from the industry. Therefore, apprenticeships, internships and on-the-job training are the way to go.

Sixth, the iPhone story shows how the PLI program can be used properly. India has obvious cost disadvantages compared to China, Vietnam and other competitors. PLI is not a subsidy, but it can help offset the quantifiable disadvantages of higher land, labor, energy and transportation costs. Due to WTO rules, it cannot explicitly reward exports. Therefore, the smartphone PLI cleverly set very ambitious production targets that could only be achieved by massively increasing exports and jobs.

Seventh, it teaches the critical importance of an objective, trust-building dialogue between the government and the company based on mutual respect. It took 15 months of patient negotiations by an open-minded team of officials and Apple executives who left their arrogant egos at the door.

The iPhone story has sent a clear message to global companies that India is no longer a hostile place for manufacturing. It is also a call to us to replicate this success in all labour-intensive sectors – apparel, footwear, toys, food processing etc. The government needs to be proactive. The Prime Minister of Vietnam even turned up at Apple’s headquarters in America to persuade the company to manufacture iPads in his country. China is constantly courting foreign companies. India’s rulers are not trained to do this. Only a handful of Indian states, mainly in the south and west, even understand this. India is competing not only with Asian countries for the role of global hub, but also with Mexico and American states like Ohio. If we succeed in doing this, it will also put pressure on us to push for economic reforms to make India competitive in land, labour and capital markets. What could be a greater prize in the end than turning a poor country into a middle class nation!

- Read more: Nara Lokesh meets Foxconn officials to push forward important job creation initiative in Andhra Pradesh

- CII: Budget 2024 meets expectations and will create jobs