From shimmering skink rainbows to iridescent metallic hummingbirds, many creatures exhibit vibrant hues created by the entanglement of wavelengths of light in nanostructures.

Researchers led by bioinformatician Aldert Zomer from Utrecht University have now identified genes that also enable bacteria to exploit this lively phenomenon.

While the colors emitted by pigments are the non-absorbed residual colors of the visible light spectrum, structural colors are created by the interference of reflected light.

The colors projected depend on how small-scale structures on the surface of a material direct light, causing some wavelengths to combine or cancel each other out. What a viewer sees can shift depending on the viewing angle, resulting in dramatic changes in color intensity or dazzling color transitions.

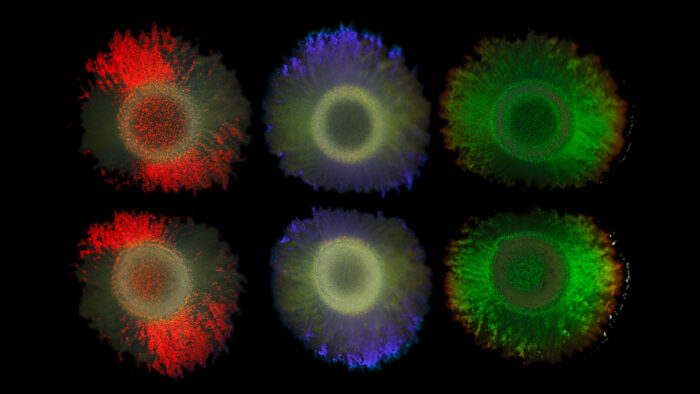

Individual microbes, such as marine bacteria Marinobacter alginolyticacan act as nanostructures by coordinating with each other and forming colonies in a precise pattern that allows them to reflect specific wavelengths.

“Structural-colored bacterial colonies are living nanostructures that manipulate light, and we have identified several molecular pathways associated with the process of their formation,” Zomer and his team write in their article.

The researchers compared the genomes of 87 bacterial strains that can form structurally colored colonies with those of 30 colorless strains to find the genetic fingerprint of this phenomenon. Using AI models, the team then examined 250,000 bacterial genomes and 14,000 environmental samples to find out which other bacteria had structural color.

Surprisingly, structural colors even appeared in bacteria that live in places where there is no light to reflect.

“We found that the genes responsible for structural color are mainly found in oceans, freshwater and special habitats such as intertidal zones and deep-sea areas,” explains Bas Dutilh, a virus ecologist at the University of Jena. “In contrast, microbes in host-bound habitats such as the human microbiome showed only very limited structural color.”

The fact that the structural color appears in the depths of the ocean suggests that the nanostructures involved probably serve other biological processes than just blinding observers. For example, they could act as defense structures against viruses or help cells to attach themselves to floating food particles, the researchers explain.

Or the structural color of bacteria could have arisen merely as a side effect of the organization of the bacteria in their colonies.

If we understand how nature creates structural colors, we could develop environmentally friendly materials with durable colors and other desirable properties, such as lightweight paint for aircraft.

This research was published in PNAS.