By Lorris Chevalier

History, as the saying goes, is written by the victors. This common saying reflects an important truth: the narratives we inherit often reflect the perspectives of those who prevailed. But what if history wasn’t just written by the victors? What if we also considered the voices of the vanquished? By including these overlooked perspectives, we might gain a richer and more nuanced understanding of the past. This article explores how the narratives of the vanquished – from the fall of Rome to the Viking invasions to the Battle of Roncevaux – can change our view of history.

When history is written by the victors, it often reflects a narrow, one-sided perspective. The victorious powers craft narratives that may serve political or ideological ends by portraying themselves as just and noble and demonizing their enemies. While these accounts are informative, they often lack nuance and fail to capture the full complexity of historical events.

However, the story told by the losers can also be ideologically motivated. While the stories of the defeated offer a counter-narrative, they are not necessarily more objective. They too can be shaped by the need to justify actions, gain sympathy, or maintain certain beliefs. Despite this bias, exploring the perspectives of the defeated is crucial to a more comprehensive analysis of history.

The voices of the defeated

The narratives of the defeated can humanize individuals who have been dehumanized or vilified in dominant historical accounts. They provide insight into the motivations, struggles, and circumstances of the losers, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of historical events. These narratives also reveal the mistakes of all involved and offer lessons that are crucial to preventing the repetition of historical mistakes.

By examining the stories of the losers, we gain a deeper understanding of the long-term impact and legacies of historical events—insights that go beyond the immediate consequences for the victors. After all, victory belongs not only to those who win battles, but also to those who shape the narrative of history.

Case Study: The Fall of Rome

The Fall of Rome, the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, is one of the most significant events in history. It marked the end of ancient Rome and ushered in profound political, social and cultural changes that would shape Western civilization for centuries. However, the story of the fall of Rome is primarily told from the perspective of the Romans themselves – the defeated.

Here are five of the most important sources:

- Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330–395), a Roman historian and soldier, offers in his work a first-hand account of the events that led to the fall of Rome Res GestaeHis writings provide insight into the military and political challenges that the Roman Empire faced during his lifetime.

- Orosius (ca. 375–418), a Christian historian, wrote Historiarum Adversum Paganoswho interpreted the fall of Rome as divine punishment for paganism. His perspective reflects the religious interpretations of his time.

- Zosimus (5th century), a Byzantine historian, described the decline of the Roman Empire and the rise of Byzantium in New HistoryHis report is notable for its critical view of Roman leadership and the impact of external threats.

- Procopius (c. 500–565), a Byzantine historian, wrote The secret historya secret report that harshly criticizes the ruling elite and their role in the decline of the empire, offering a unique and often controversial perspective.

While these accounts are invaluable, they are limited by their perspective. There are no primary sources to inform us about the peoples who invaded Rome. The absence of the victors’ voices in these accounts shapes our understanding of this event and its reception, particularly in terms of how it influenced the medieval awareness that the world is finite and heading toward its imminent end.

Case Study: The Vikings

The Viking invasions of England and Paris are other examples where the perspectives of the defeated dominate the narrative. A remarkable first-hand account of the Viking invasions of England comes from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Compiled over several centuries, this chronicle provides contemporary accounts of Viking raids and invasions of England from the late 8th century onwards. The entries vary in detail and perspective and provide a valuable historical record of events.

As for the Viking invasions of Paris, the main source is the Annals of Saint Bertinwhich contains a detailed account of the siege of Paris in 845. Fulda Annals also provide additional insight into Viking activities in the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century. These annals were contemporary historical accounts written by scholars and chroniclers of the time.

However, apart from archaeology, there are very few sources from the Viking perspective. Their lives are reconstructed in a mosaic-like manner through the eyes of Westerners, often biased by the civilizational lens that portrays the barbarian as inherently savage. The vision of the shaggy, muscular, primitive Viking is fed entirely by these sources and offers a limited and often distorted view of Viking culture.

Case Study: The Battle of Roncevaux

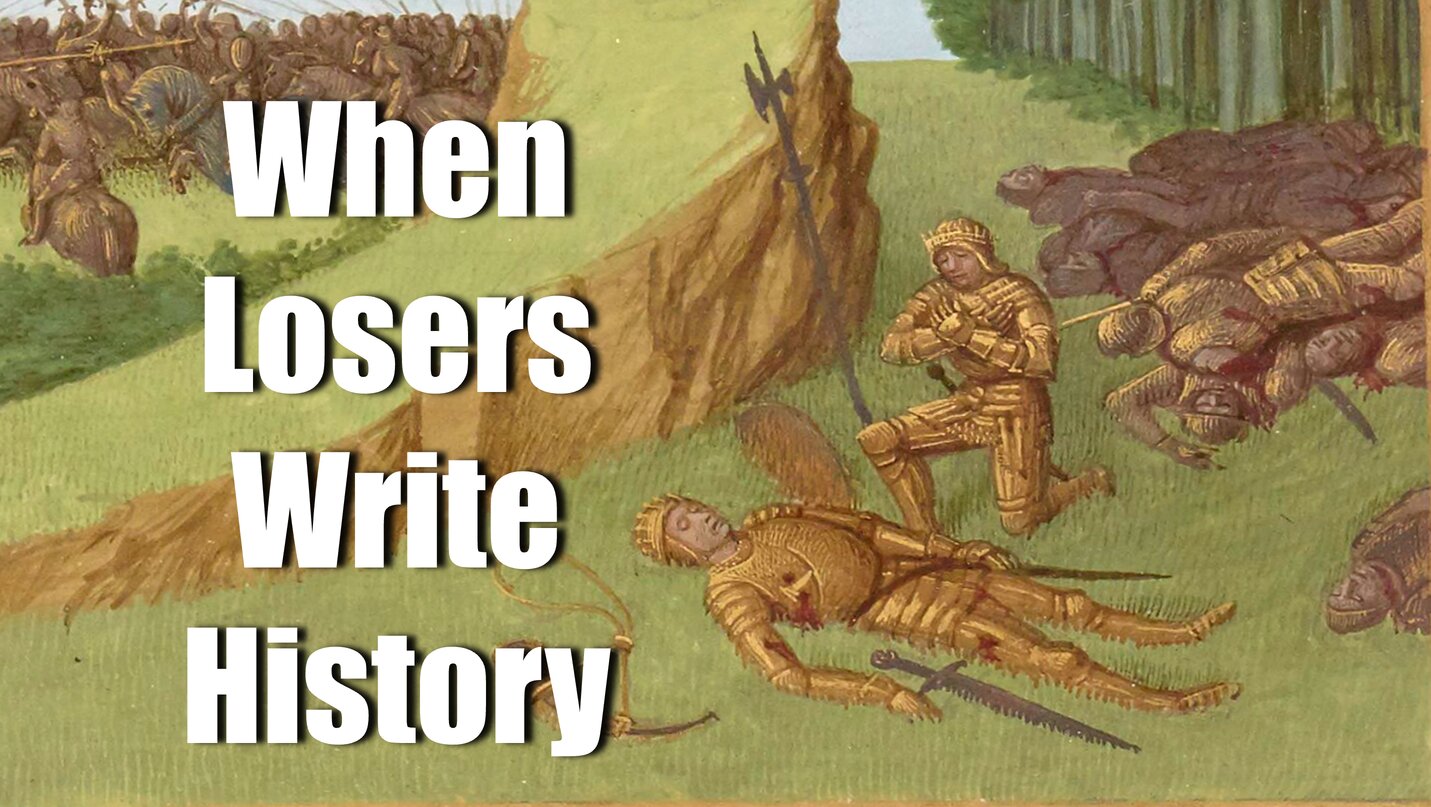

The Battle of Roncevaux in 778 is best known from the Song of Roland (The Song of Roland), an Old French epic poem. The authorship of the poem is unclear, but it is attributed to a poet named Turoldus or Turold. The Song of Roland is acHanson de Gestea type of medieval epic poem that recounts the heroic deeds and tragic events, including the Battle of Roncevaux, during Charlemagne’s campaign in the Iberian Peninsula. Although the poem is a literary work rather than a historical chronicle, it offers insights into the cultural and literary aspects of the period and the ways in which events were remembered and represented.

This struggle, best known through this literary text, is an example of how the narratives of the losers can be ideologically shaped. Song of Roland depicts Muslims with certain, sometimes stereotypical characteristics, reflecting the Christological ideology of repentance and suffering for others. This representation is a reminder that even the narratives of the defeated can be shaped by the need to maintain certain cultural and religious beliefs.

![]()

Why did people in the medieval West write their history even when they suffered defeat? Recording historical events, even defeats, is a way for societies to preserve their identity and cultural heritage. It helps them understand their origins, the challenges they faced, and the lessons they learned from them. Understanding the reasons for failures also helps make better decisions in the future and avoid similar pitfalls.

These stories become part of a collective consciousness that shapes the narrative of a nation’s past and fosters a sense of shared history among its people. Documenting defeats often involves acknowledging the sacrifices made by individuals and communities during difficult times. This helps to celebrate the resilience and bravery of those who faced adversity. Therefore, documenting defeats holds leaders and decision-makers accountable for their actions, allows for critical scrutiny of past decisions, and contributes to more transparent and accountable governance.

Writing about history, even when it involves defeat, is a form of cultural expression. It reflects the way a society interprets and communicates its past, shaping its cultural narrative and promoting a sense of continuity. The decision to deliberately report on defeat can be attributed to a cultural trait inherent in medieval Christianity. The idea that defeat is perceived as good, in the image of Christ who achieved victory through his cross, illustrates this paradox. So, as the saying goes, “the last will be first,” defeat can actually become victory.

Dr. Lorris Chevalier has a PhD in medieval literature and is a historical consultant for films including The final duel And Napoleon.

Upper image: The Death of Roland, depicted in BnF MS Français 6465, fol. 113