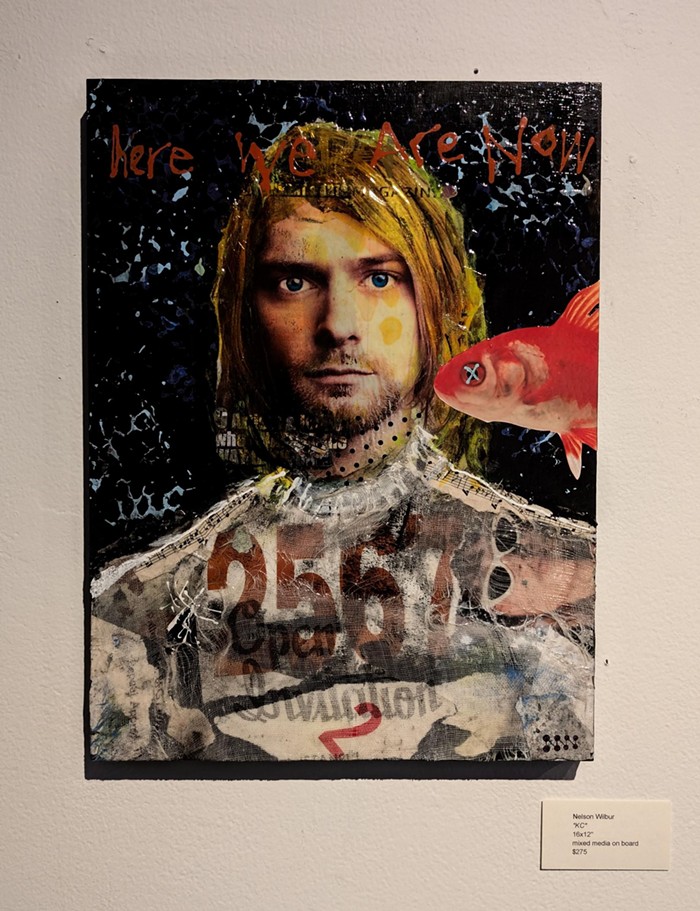

There he was again, Kurt Cobain. This time, staring intensely (almost accusatory) at the top of a mixed-media collage by Nelson Wilbur. It’s called “KC,” and is part of an exhibition at the Vermillion Gallery featuring works by artists associated with Fogue™ Studios & Gallery in Georgetown. I looked at “KC” for several minutes (the iconic sunglasses, stripes of musical notes, words from Nirvana’s biggest hit “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the mysterious number 2567), and then spent several minutes wondering why I always stop and stare at every work featuring the late rock star. “KC” is undoubtedly a beautiful piece of art, but if it weren’t for that subject, I would have moved on to the next Wilbur work. Cobain’s painting always presents me with a puzzle that I try to solve but never manage to. Is it his eyes? The reddish fish in “KC” almost kisses him. Why?

Late the following day, August 11, I learned that Seattle’s famous rock critic Charles Cross had died in his sleep.

The unexpected death of Seattle’s most prolific music journalist and historian, Charles R. Cross, has been on my mind for the past few days.

I met with him at home a few months ago to talk about his career, music and Kurt’s legacy.

Rest in peace, Mr. Cross. I miss you.💙 pic.twitter.com/uMNUswIHoz

— Matt M. McKnight (@mattmillsphoto) 14 August 2024

Cross is the author of the definitive Cobain biography, Heavier than the skywhich was published in 2001. In 2008 (or thereabouts), I met him at a dinner party organized by PopCon, and we talked endlessly about Sister Rosetta Tharpe. In 2019, Cross suggested on Facebook that the city of Seattle buy Kurt Cobain’s former home on Lake Washington Boulevard—which was then for sale and listed for $7.5 million—tear it down, and turn the property into a park connected to the park, with the bench becoming a Cobain shrine. In fact, it’s now called the Kurt Cobain Memorial Bench. On and around it, you’ll always find flowers, notes, loving graffiti. People from all over the world visit it. Some even experience what can only be described as religious (“I dealt with my midlife crisis by visiting Kurt Cobain’s shrine in Seattle…”)

Unfortunately, our city hasn’t had time for such conversations. City Hall is painfully pragmatic. Council rarely lets voices guide it. Cross be damned. Cobain’s house was recorded as selling for $7,050,000 during the not-quite-long lockdown. It’s now another of Seattle’s many missed opportunities.

“It is possible for a thing you own to lose all its private value and become valuable only to the public,” I wrote in a Slog Post, who went out of his way to support Cross’s proposal. “For example, could you imagine selling the real Roman wooden cross that Jesus was nailed to? Could you imagine putting it on the market? And putting it in someone’s house? Something similar can be said about Cobain’s house. It is valuable to millions and millions of people whose lives are tied to the music and life of Kurt Cobain.”

What I haven’t mentioned in this post is our city’s inability to name and elevate its secular gods. Consider the Museum of Pop Culture. The late city leader Paul Allen built it as a church for Jimi Hendrix, the subject of Charles Cross’ biography. A room full of mirrors. Star architect Frank Gehry had designed it to look like a guitar that Hendrix had set on fire. But the neo-church never really came to fruition. The believers never came. Eventually the reference to Hendrix, Experience Music Project, was reduced to Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum, and finally “Experience” was left out altogether, as was the part about science fiction, and the current generic name was adopted.

The statue of Jimi Hendrix on Broadway is a joke. The Starbucks cafe, dedicated to the once thriving jazz scene in Jackson, closed long ago and still stands empty. It’s hard to believe that “a young Ray Charles had a regular gig at The Rocking Chair nightclub near 14th Avenue and East Yesler Way.” And let’s not talk about Ernestine Anderson. Kurt Cobain, a god of the rock world, had no chance in such conditions. He was lucky to get a bench. Our grunge dead have almost no shrines, monuments, meccas. Why?

When I flew into Memphis in 2017, I was stunned to find that the Mississippi Delta did indeed glow “like a national guitar.” Paul Simon was right. He wanted to go to Graceland. I wanted to go to Graceland. But as I later found out, the whole city is devoted to its pop music gods. One bar at a time, Beale Street (which Jackson didn’t become), the Stax Museum of American Soul Music (which the Museum of Pop Culture didn’t become)—Memphis shows its enthusiasm for idolizing the mundane at every opportunity. In fact, one of the biggest stories and controversies to come out of Memphis in recent memory revolves around Graceland. Poor Lisa Marie Presley died; she was in debt, of course; the house she left behind was now on the market. The city said no.

On a Tuesday in May, a judge in Memphis, Tennessee, stopped at the last minute the trial that could have resulted in the famous estate of Elvis Presley being auctioned off to the highest bidder. The whole episode was surreal and seemed like a sad aftermath to the death of Lisa Marie Presley, the King of Rock and Roll’s only child, who had died 16 months earlier.

Why don’t we, as a city, feel that way about the house on Lake Washington Boulevard? Cross certainly did. Seattle doesn’t. Unlike Memphis, we seem to lack that sense of urgency or understanding that certain parts of our culture are supernatural. It’s almost impossible for us to spiritualize the material. We just can’t. How does one explain this appalling lack? Perhaps Gene Balk has the answer: “Seattle is the least religious major city in the United States.” Is that what it boils down to? Toots & The Maytals’ call to “feel the spirit” is lost on us nonbelievers? Wilbur’s Kurt Cobain’s eyes looked angry to me.