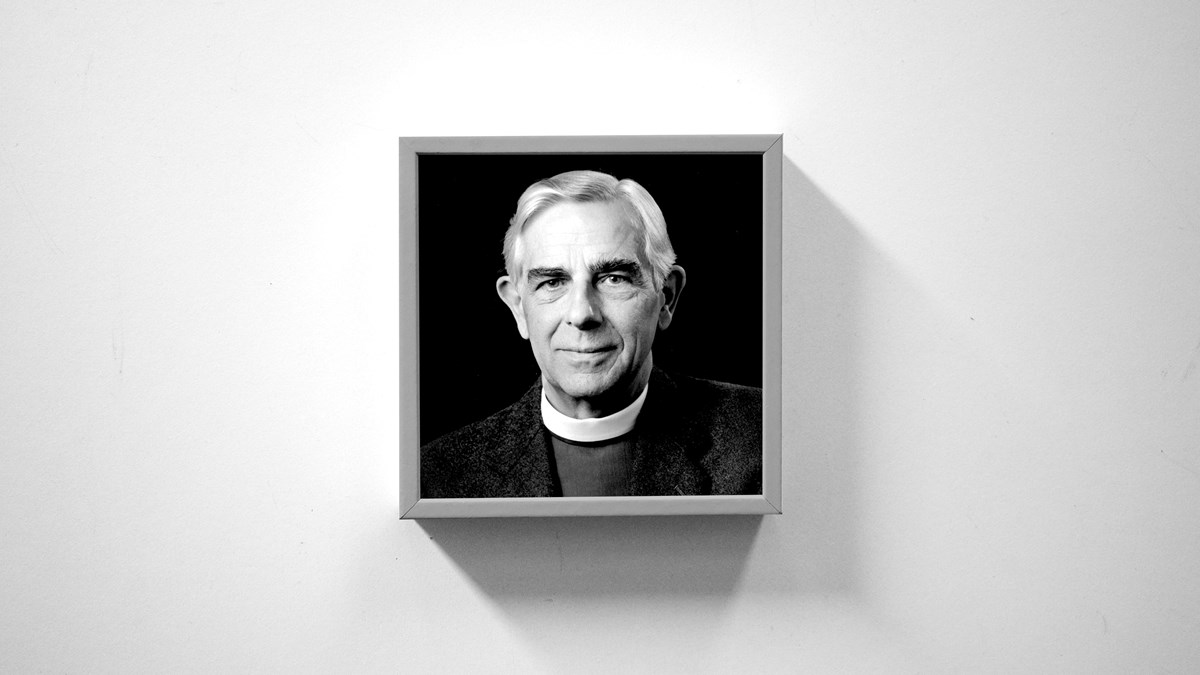

Timothy Dudley-Smith, author of “Tell Out, My Soul,” “Lord, for the Years,” “Sing a New Song” and more than 400 other hymns, died on August 12 in Cambridge, England. He was 97 years old.

Dudley-Smith was a bishop in the Church of England and served as suffragan, or assistant, of Thetford in Norwich for 12 years before retiring in 1991. Before taking on a leadership role, he was a director of the Church Pastoral Aid Society.

However, he was always better known for his hymns. Many Anglicans valued his words very much.

“These hymns restore our faith not only in the gospel, but in the act of singing that gospel together with heart, soul and voice,” wrote a retired Durham University English professor in 2006. “Dudley-Smith never lets us down. There are no weak lines, no vague rhymes, no distortions of syntax, no botched meters… no bad hymns.”

Dudley-Smith’s most popular hymn, “Tell Out, My Soul,” has been published 190 times in the UK and is also popular in the US and elsewhere. First written in 1961, it appeared in 42 percent of all contemporary hymnbooks by 1985, according to hymnary.org.

Ten of Dudley-Smith’s other songs have been published more than two dozen times. “Faithful Vigil Ended” – “Faithful vigil ended / watching waiting cease / Master, grant thy servant / his discharge in peace” – has appeared in 28 different hymnals. “Name of All Majesty,” written in 1979, has appeared in more than 70 different hymnals, including translations into French, Korean and Chinese.

Dudley-Smith was a committed evangelical and had identified with evangelicalism since childhood, but his work was accepted across party lines in the Church of England.

Ian Bradley, a church historian, hymn editor and BBC journalist, wrote that Dudley-Smith represented “a very orthodox Anglican tradition of hymn writing” and was “unashamedly evangelical.” At the same time, according to Bradley, his work was seen as “very English” and somehow “broad enough to include Noël Coward, WS Gilbert, Stephen Sondheim and Shakespeare, as well as JI Packer and Martyn Lloyd-Jones.”

Dudley-Smith, for his part, was often very modest about his hymns. He often remarked that he was not actually musical and had not written music, but only the metrical poetry that could fit various singable tunes. He titled his 2017 book on hymn writing A functional art.

“Not all our hymn texts will be, or should be, Rolls-Royces,” wrote Dudley-Smith, “but they should all be reasonably roadworthy, and as faithful to the Scriptures, as free from error, as carefully constructed, as appealing to the imagination, heart and will, and as user-friendly as possible.”

Dudley-Smith was born in Manchester on Boxing Day, 26 December 1926, to Phyllis and Arthur. His father was a teacher and often read poetry to his children, often putting them to bed with verses by AE Housman, Walter de la Mare and Alfred Tennyson:

Even if much is taken, much remains; and even if

We are no longer the strength we had in ancient times

Moving earth and sky, what we are, we are;

An equanimous nature of heroic hearts,

Weakened by time and fate, but strong in will

Strive, seek, find and do not give in

This trinity of Victorian poets became his favourites, followed by 20th-century British figures such as TS Eliot, Philip Larkin and John Betjeman.

When Dudley-Smith was eleven years old, his father died. He later recalled that this was a defining moment for his faith.

“I prayed when I knew he was sick, and you would think that if my prayers didn’t change the situation, it would have deterred me,” he said in an interview. “But that didn’t happen. It showed me that I need a heavenly father.”

At about the same time, Dudley-Smith decided he wanted to become a minister.

“Someone asked me at a family tea party (as was the custom in those days): ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ I said: ‘I’m going to be a minister.’ It just came out like that. It was the first time I had heard of it!” he said.

Dudley-Smith was active in the Scripture Union and learned about the Bible through the group’s children’s programs. His faith was strengthened at a summer camp for boys run by conservative Church of England evangelical minister EJH Nash.

When he went to Cambridge, he considered training in mathematics and education like his late father, but ultimately decided on theology. He studied at Pembroke College and then completed ordination training at Ridely Hall, both in Cambridge.

Dudley-Smith was ordained a deacon in 1950 and a priest in 1951. His bishop – a former Olympic athlete and rugby player known as “the flying vicar” – sponsored the evangelist Billy Graham’s trip to England in 1954 and encouraged Dudley-Smith to get involved. The young vicar helped transport hordes of schoolboys to the racecourse in north London where Graham preached for four weeks, then extended his stay by two more months by popular demand.

The following year, Dudley-Smith joined the staff of the Evangelical Alliance and became editor of the organization’s magazine, crusade.

His journalistic work was praised by the priest in charge of the BBC’s religious broadcasts. The magazine was “something quite new in religious journalism in Britain. It was a glossy magazine… it had cartoons and a sense of humour and it mixed religious material with commentary on world events and – the innovation discovered by its editor – serious poetry.”

Dudley-Smith’s love of poetry was well known to his colleagues and he also wrote his own verse. He had considered writing songs but rejected the possibility.

“I’m completely unmusical!” he said. “I can’t sing properly and I often change keys without realizing it.”

But in the early 1960s, a priest was working on the new Anglican Hymnal approached him and asked him if he wrote hymns. When he said no, the priest said, “Have you written any verses that could be turned into a hymn?” And the answer was yes.

Dudley-Smith had commissioned someone to print the New English Bible for the crusade and happened to read Mary’s hymn, the Magnificat, in Luke 1.

“Her version of Mary’s song begins, ‘Declare, O my soul, the greatness of the Lord,'” Dudley-Smith later recalled. “I said to myself, ‘That’s a verse,’ and wrote four short verses.”

It became his first and most popular anthem:

Declare, O my soul, the greatness of the Lord!

Countless blessings, give my soul a voice;

fulfill to me the promise of his word;

In God my Savior my heart shall rejoice.

However, the editors of the hymnal initially set the hymn to a tune that didn’t work. At a conference of 600 clergy who went through the hymns, people actually stopped singing the hymn halfway through. Then they set the words to Woodlands, a tune composed in the early 1900s, and that worked. The hymn was well received and widely sung.

The poet Betjeman said it was “one of the few modern hymns that will really endure”.

The editors of the new Anglican Hymnal suggested other religious subjects for Dudley-Smith to write about, and he made hymn writing a regular part of his life and ministry. He published a volume of his hymns in 1966 and another in 1969. Together they have sold over a million copies.

Because of his enormous output, he was compared to Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley and some contemporaries celebrated him as the greatest Protestant hymn writer of his time.

Dudley-Smith’s daughter Caroline Gill remembers that he wrote most of the hymns while on holiday in Cornwall.

“My father would rise early to pore over his Bible and write in his manuscript book, which contained bits of text that had accumulated over the year and was just waiting to be made into hymns,” Gill wrote. “My father would occasionally work on a text on the beach, between a pie lunch and an afternoon surfing trip.”

Although he wrote a lot, it was not always fluent. He wanted his hymns to be simple and profound, heartfelt and clear, biblical but uncontroversial. Too much repetition made him wince, and he also shied away from vague rhymes like sin And kingHe described his process as slow, careful and laborious.

“I think you have to expect that you’ll get two lines out of a few hours’ work,” he once said, “and then discard them again when you go through it afterwards.”

But the work was worth it because the hymns had a great impact on people’s lives.

“Many people learn more theology from hymns than from other sources,” Dudley-Smith said. “They allow for communal participation in a unique way, allowing for collective expression of praise, repentance, devotion and a whole host of other things. Also, I think hymns offer many people an opportunity to express feelings that are close to their hearts but that they would find difficult to put into words.”

Dudley-Smith’s second most popular hymn, “Lore, for the Years”, became popular at New Year services and anniversaries of the Church of England. It has also been used to celebrate national religious ceremonies in Britain, including the enthronement of the Anglican Archbishop in 1991 and the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II in 2002.

In 2003 he was appointed Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for his “services to the art of hymns” – a rank far below knighthood.

Dudley-Smith also wrote an authorized two-volume biography of the evangelical leader John Stott, who was a personal friend. Volume 1 was titled John Stott: How a leader is created; Vol. 2, John Stott: A Global MinistryHe edited an anthology of Charles Wesley’s hymns and a collection of English hymns, and continued to write his own hymns even in retirement.

“Writing hymns has been an extremely enriching and totally unexpected gift for me,” he said.

He called it “the best of all deals.”

Dudley-Smith’s wife June Arlette MacDonald died in 2007 after 48 years of marriage. He is survived by his daughters Caroline Gill and Sarah Walter, and his son James Dudley-Smith, who succeeded him as a minister in the Church of England.