Ride were one of the most powerful and original bands on the British shoegaze scene. Duncan Greive watches their evolution and wishes he hadn’t.

It’s almost impossible to age gracefully. Earlier this year, I had a swollen fluid sac oozing out of my elbow for a few months. A friend gets numbness in her fingers when she sleeps in the wrong position, while another fell for the first time, “and it felt like an old person falling.” We’re all in our mid-40s.

When we saw Ride at the Powerstation, we were inevitably confronted with this reality, because the band has grown in ways that the audience was certainly not aware of.

Formed in Oxford in the late ’80s, Ride quickly signed to Creation, the indie label that would dominate the ’90s with bands like Oasis and Primal Scream. Shoegaze – a genre epitomised by bands like My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive – was a moody, arty music that never really reached a mass audience. It was displaced by grunge and then swept away by the unstoppable rise of Britpop, but has recently enjoyed a huge revival, fuelled by its popularity on TikTok, with its textures and hazy, soulful sound fitting the current global mood.

In any consideration of the most perfected albums of the ’90s, Ride’s debut, Nowhere, has to rank near the top. It relies on Andy Bell’s guitar, alternately menacing and shimmering, and Loz Colbert’s powerful drumming, with Bell and Marc Gardener taking turns singing in hauntingly squeaky, post-pubescent keys.

It was Nowhere and its sequel, Going Blank Again, that drew a sizeable but not overwhelming crowd – mostly men, average age in their early 50s – to the Powerstation on a wet and windy Sunday night. We were young when those records came out; they meant everything to us. We’re older now and those songs still have the same power to remind us of when our stories weren’t written, when our identities were shaped by knowing and loving Nowhere more than Nevermind.

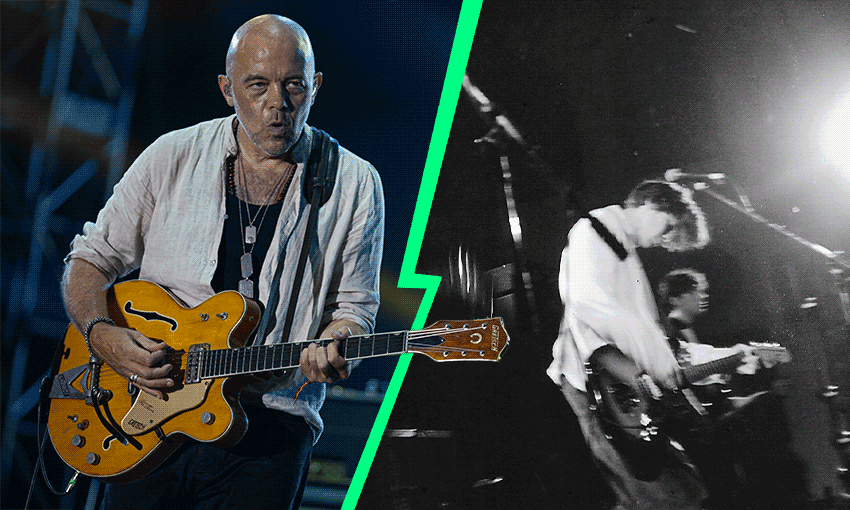

We waited for this in this beautiful hall full of excitement. Ride came on stage at 9pm sharp. It was immediately clear that something was different – at least in the image we had in our heads. The press photos from that time were full of fringes, baggy jeans and enigmatic, withdrawn personalities. Three quarters of the band dealt with this feeling in a serious and reserved manner. Andy Bell even had a perfect bowl cut, although his hair had now turned completely grey.

Singer and guitarist Marc Gardener was a problem, though. For a genre that demands that you scrutinise your footwear, his were laceless and pointed, like in Chapel Bar. Around his neck he wore a chunky pearl necklace and at least two dog tags, despite not having served a tour of duty. He wore a blazer. All of this is fine out of context – you have to be cute to be yourself – but it was hard not to interpret it as a betrayal of what Ride stood for. It was as if Jez from Peep Show had taken over the band.

That should be fine, even admirable, because of course he has changed! In the past few years we have all grown up. We have become teachers, lawyers, car salesmen and some unlucky ones even journalists. We are not trapped in our teenage selves. But we expect that from bands.

This is the inevitable tension at the heart of the growing and increasingly lucrative nostalgia scene: the audience wants the artist to do something that is completely unnatural; something that is in some ways at odds with the modern, groundbreaking origin story of many artists. We want you to take us back to our youth by embodying and performing your best impression of your young self.

Still, there is growing up, and then growing into the image of the artist you’ve implicitly decided against. In 1992, Ride’s mystique, its wall of noise, and its lack of concession to a clean, radio-friendly sound seemed both symbolically and sonically powerful. It was jarring to hear the band largely abandon that approach.

The first half of the set was dominated by songs from their latest album, Interplay, which Gardener believes is the best the band has ever recorded, despite evidence to the contrary (to be honest, most artists are stuck in that belief system). The studio versions of these songs are passable. Pitchfork’s review sums it up well when he says the band “refuse to give in to their classic sound. Their attitude is frustratingly commendable – a creative tenacity that one can admire with a somewhat heavy heart.” They’ve abandoned the thunderous, emotive guitars in favor of dull, competent synth rock.

Live, they shapeshift again, and it’s not good. The band they are most remembered for today is Jesus Jones. The last time Jesus Jones’ name was mentioned in this country was when The Feelers were commissioned to cover Right Here, Right Now for the 2011 Men’s Rugby World Cup – perhaps the most glaring act of cultural embarrassment of this century. Jesus Jones is fine; but they were the exact opposite of what Ride stood for.

It hits its lowest point during Peace Sign by Interplay. In truth, Ride’s lyrics were mostly just OK – but that didn’t matter because you felt them more than you heard them. Since then, they’ve been on a downward spiral. The chorus of Peace Sign goes:

“Give me a peace sign

Throw your hands in the air

Give me a peace sign

Let me know you’re there”

This new sound is strange enough on the new songs, but when Gardener sings Dreams burn down as if it were The world I knowcomplete with messianic gestures, it’s breathtakingly strange. It’s as if he’s trying to reinterpret these beautiful, brittle songs as pre-Oasis pub rock.

Things get more exciting during the long run of early material, especially as Bell – wearing a nice black T-shirt and Adidas Gazelles, perfect – takes on more lead vocals. Songs like Kaleidoscope, Taste and the sublime Vapour Trail give us what we wanted. But even when the sound is right, Gardener’s trademark rock star gestures are in stark contrast to the band’s sound and philosophy we wanted to see.

It forces you into a strange dilemma. Gardener seems happy to be on a stage, and in interviews convinced that the music he’s making now is the closest thing to the vision they’ve always had. And yet it feels like a conscious denial of what brought us all here in the first place. The incongruity is hard to shake, even if now, 12 hours later, I’m still not sure which of us is wrong: him, because he’s grown and changed, or us, because we wish he wouldn’t.